Introduction

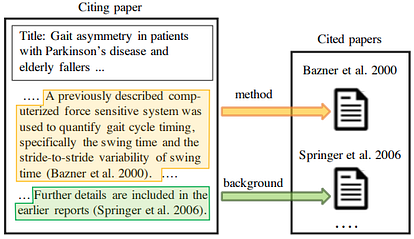

Machine reading and automated analysis of scientific literature have increasingly become important due to information overload. Citations are typically used to measure the impact of scientific publications (Li and Ho, 2008)[1]. Citation Intent Classification is the task of identifying why an author cited another paper. The automatic identification of citation intent could also help users in doing research. FIGURE 1 shows an example of two citation intents. Some citations indicate direct use of a method, while others may acknowledge prior work or compare methods or results. Existing models are based on hand-engineered features, which may not sufficiently model signals in the text (e.g. linguistic patterns or cue phrases). Recent advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP) have introduced large, contextual representations that are obtained from textual data without the need for manual feature engineering. Cohan et al. (2019)[2] introduce a novel framework to include structural knowledge into citations as well as a new dataset of citation intents: SciCite.

Figure 1: Citation intent example. Source: Cohan et al. (2019)

Dataset

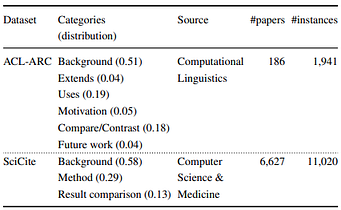

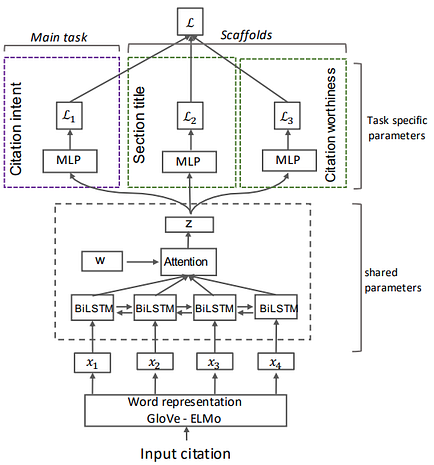

SciCite is five times larger, contains fewer but more general categories, and covers scientific literature from more general domains than existing datasets such as ACL-ARC (Jurgens et al., 2018)[3]. FIGURE 1 compares the datasets. The papers for SciCite were sampled from the Semantic Scholar corpus. The authors chose more general categories as some are very rare and would not have been enough for training. Citations were extracted using science-parse. The ACL-ARC dataset, which consists of Computational Linguistics papers, was annotated by domain experts in NLP. The training set for SciCite was crowdsourced using the Figure Eight platform, while the test set was annotated by an expert annotator.

Table 1: SciCite vs ACL-ARC. Source: Cohan et al. (2019)

Model

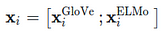

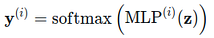

The proposed neural multitask framework consists of a main task (Citation intent) and two structural scaffolds, or auxiliary tasks: section title and citation worthiness. The input x is the set of tokens in the citation context, which are encoded by concatenating non-contextual word representations GloVe (Pennington et al., 2014)[4] with contextualized embeddings ELMo (Peters et al., 2018)[5] (Eq. 1).

Eq. 1

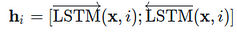

The encoded tokens then get fed into a bidirectional long short-term memory (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997)[6] network with hidden size d₂, which results in the contextual representation of each token w.r.t. the entire sequence (Eq. 2).

Eq. 2

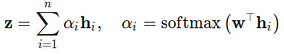

Finally, an attention mechanism is added, which produces a vector representation of the input sequence (Eq. 3). w is a parameter served as the query vector for dot-product attention.

Eq. 3

The citation worthiness task is to predict whether a sentence needs a citation. The hypothesis is that language in sentences with citations is different from regular sentences in scientific work. Sentences with citations are positive samples and sentences without citation markers are negative samples. This task could also be used in a different setting (e.g. paper draft aid).

The section title task is to predict the title of the section in which the citation appears. The hypothesis here is that citation intent is relevant to its section. Contrary to the other tasks, the authors use a large number of scientific papers to generate the training data for this task.

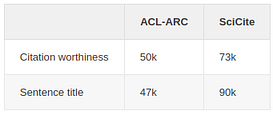

In the multitask framework, a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) followed by a softmax layer is used for each task (Eq. 4). The class with the highest probability is then chosen.

Eq. 4

Figure 2 shows an overview of the proposed model.

Figure 2: Model overview. Source: Cohan et al. (2019)

Preprocessing

For the citation worthiness task, citation markers were removed in order for the model to not “cheat” by simply recognizing citations in sentences. For sentence title, citations and their contexts were sampled from the corpus. Section titles were normalized with regular expressions to the following general categories: introduction, related work, method, and experiments. Titles that did not map to these were removed. The table below shows the total number of instances for each of the datasets and tasks.

Experiments

The proposed model, trained with standard hyperparameters, is compared to a strong baseline and a state-of-the-art model. The first baseline is a BiLSTM with an attention mechanism (with and without using ELMo embeddings) that only optimizes for the citation intent classification task. This is meant to show if the structural scaffolds and contextual embeddings, in fact, improve performance. The second baseline is the model used by Jurgens et al. (2018)[3], which had the best-reported results on ACL-ARC. The authors incorporate a diverse set of features (e.g. pattern-based, topic-based, prototypical argument) and train a Random Forest classifier.

Results

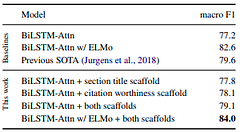

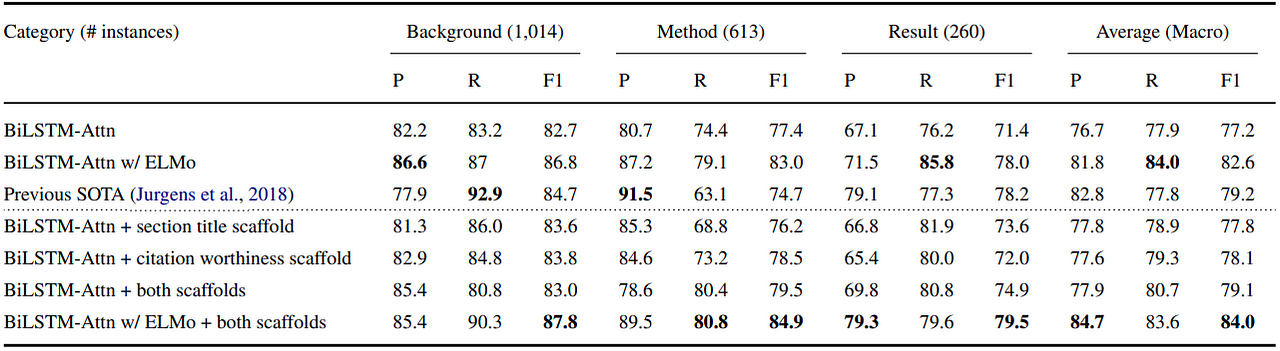

The results on both the ACL-ARC (FIGURE 2) and SciCite (FIGURE 3) datasets indicate that the inclusion of structural scaffolds improves performance on all of the baselines. The performance differences for the respective datasets is partly due to the different dataset sizes. Each auxiliary task contributes slightly over the baseline, while the combination of both tasks shows a large improvement on ACL-ARC and a marginal improvement on SciCite. The addition of contextual embeddings further increases performance by about 5% macro F1 on both datasets (including on the baselines).

Table 2: Results on ACL-ARC. Source: Cohan et al. (2019)

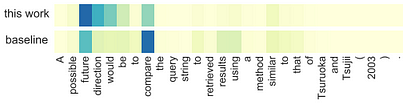

Table 3: Results on ACL-ARC. Source: Cohan et al. (2019) Figure 3 shows an example sentence from ACL-ARC for which the correct label is Future Work. The best-proposed model predicts this correctly, attending over more of the context, while the baseline predicts Compare. The attention is stronger on “compare” for the baseline, ignoring the context of its use.

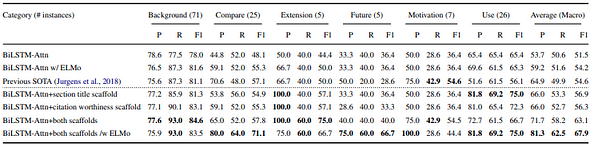

Figure 3: Example from ACL-ARC. Source: Cohan et al. (2019) When looking at each of the categories independently, categories with more instances show higher F1 scores on both datasets (FIGURES 4 and 5). Recall seems to suffer from a limited number of training instances.

Table 4: Per category classification results on ACL-ARC. Source: Cohan et al. (2019) Because the categories in SciCite are more general, there are more training instances for each. The recall on this dataset is accordingly higher.

Table 5: Per category classification results on SciCite. Source: Cohan et al. (2019)

Conclusion

Cohan et al. (2019)[2] show that structural properties of scientific literature can be useful for citation intent classification. The authors argue that relevant auxiliary tasks can help improve performance in multitask learning. The main contributions of this work are the following: (i) A new scaffold framework for citation intent classification. (ii) A new state-of-the-art of 67.9% F1 on ACL-ARC (an increase of 13.3%). (iii) A new dataset of citation intents: SciCite.

Future Work

While the current work uses ELMo, Beltagy et al. (2019)[7] show that incorporating BERT, a large pre-trained language model, which they fine-tuned on scientific data, increases performance further. A possible extension could be to adapt the model to other domains (e.g. Wikipedia).

Further reading

SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text — Beltagy et al., 2019 ScispaCy: Fast and Robust Models for Biomedical Natural Language Processing — Neumann et al., 2019 Original post here.

References

- [1]: Zhi Li and Yuh-Shan Ho. 2008. Use of citation per publication as an indicator to evaluate contingent valuation research. Scientometrics.

- [2]: Arman Cohan, Waleed Ammar, Madeleine van Zuylen, and Field Cady. 2019. Structural scaffolds for citation intent classification in scientific publications. In NAACL-HLT, pages 3586–3596, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [3]: David Jurgens, Srijan Kumar, Raine Hoover, Dan McFarland, and Dan Jurafsky. 2018. Measuring the evolution of a scientific field through citation frames. TACL, 6:391–406.

- [4]: Jeffrey Pennington, Richard Socher, and Christopher Manning. 2014. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In EMNLP, pages 1532–1543.

- [5]: Matthew E. Peters, Mark Neumann, Mohit Iyyer, Matt Gardner, Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, and Luke S. Zettlemoyer. 2018. Deep contextualized word representations. In NAACL-HLT.

- [6]: Sepp Hochreiter and Jurgen Schmidhuber. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation.

- [7]: Iz Beltagy, Arman Cohan, and Kyle Lo. 2019. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. CoRR, abs/1903.10676.