Introduction

The BERT architecture and pre-training strategy set the de facto standard for how to generate rich token embeddings utilising an enormous corpus. Its architecture lends itself to be adopted for different kinds of tasks, either through adding task specific tokens in the input or task specific networks to the end of the model, utilising its token embeddings. These modifications allows us to use BERT for, just to name a few, classification, regression and sentence similarity.

In order to measure the similarity between two sentences with BERT would we concatenate them with a [SEP] token in between and feed this sequence through BERT. We can then at the other end use the [CLS] token as input to a simple classifier or regressor to tell us how these sentences are related. This process might not sound computationally complex, which is because it in the grand scheme of things isn’t. This way of measuring sentence relation only becomes an issue in real-world scenarios where such is useful. There are two main scenarios

- Finding the two most similar sentences in a dataset of n. This would require us to feed each unique pair through BERT to finds its similarity score and then compare it to all other scores. For n sentences would that result in n(n — 1)/2. This turns out to be a real problem if you are trying to integrate this in a real time environment. A small dataset of only 10.000 sentences would require 49.995.000 passes through BERT, which on a modern GPU would take 60+ hours! This obviously renders BERT useless in most of these scenarios

- Performing semantic search. This task entails finding the most similar sentence in a dataset given a query. Ideally, this would be done by comparing the query to all existing sentences, with for a dataset of n sentences would require n comparisons. Since BERT has to process each of these pairs would it for the same modest dataset of 10.000 sentences take 40+ seconds just to generate the results of a single query. I know for a fact that you would close or refresh the site if google took 40 seconds to return your search results. Again, computational complexity renders BERT unusable for this scenario.

To sum up, asking BERT to compare sentences is possible but too slow for real time applications. The main culprit is that BERT needs to process both sentences at one in order to measure similarity.

What if we could pre-compute representations (embeddings) for each sequence in our dataset separate from all other ones? These embeddings could in a second step then be used to measure, for example, similarity using the cosine similarity function which wouldn’t require us to ask BERT to perform this task. Seems like a simple enough solution, which is exactly what has been explored in Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks by Nils Reimers and Iryan Gurevych.

I will in the following sections describe their approach for creating rich sentence embeddings using BERT as their base architecture, how this extended model is trained and what their findings were.

Note: Quora is a real world example of where measuring similarity is useful outside information retrieval. Their use-case is to make sure there are no duplicated questions on their site, so that users would not have to dig through multiple question-threads asking the same thing just to find their answer. This use-case, to alert a person asking a question that there might already exist a similar question with an answer, also requires the algorithm to be fast. You can read more about how they approached this problem in 2017 in this article, which, after reading my article, probably gives you some ideas into how it can be solved with todays tools.

How does SentenceBERT work?

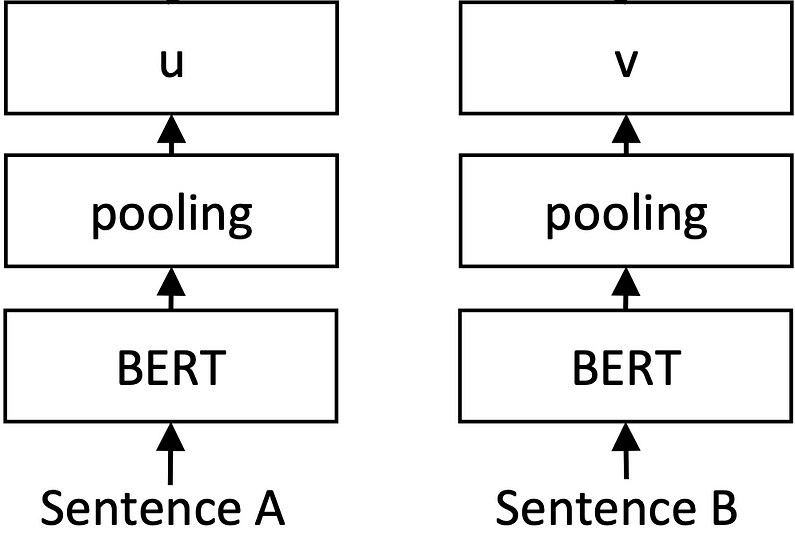

Let’s start by looking at the architecture of SentenceBERT, which I will call SBERT from here on. SBERT is a so called twin network which allows it to process two sentences in the same way, simultaneously. These two twins are identical down to every parameter (their weight are tied), which allows us to think about this architecture as a single model used multiple times. (I think the reason for the twin formulation is due to mathematical ease, but I need to read the original paper for figuring it out)

Twin network architecture of SentenceBERT

It becomes apparent from the image that BERT makes up the base of this model, to which a pooling layer has been appended. This pooling layer enable us to create a fixed size representation for inputs sentences of varying length. The authors experimented with different pooling strategies; MEAN- and MAX pooling or utilising the CLS token BERT per default already generates. How these perform and compare will be discussed later.

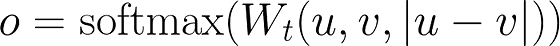

Since the purpose of creating these fixed-size sentence embeddings was to encode their semantics did the authors fine-tune their network on Semantic Textual Similarity data. They combined the Stanford Natural Language Inference (SNLI) dataset with the Multi-Genre NLI (MG-NLI) dataset to create a collection of 1.000.000 sentence pairs. The training task posed by this dataset is to predict the label of each pair, which can be one of “contradiction”, “entailment” or “neutral”. Classification was enabled by their classification specific objective function, where u and v are sentences in a pair.

Classification objective function. u and v are sentence embeddings which are concatenated before multiplication with W.

For completeness can we put base architecture and objective function together which create the SBERT model overview shown below.

SentenceBERT twin architecture configured for classification.

Related work

To better understand the contribution of SBERT can it be helpful to look at related works. I will in this short section try to give an overview of two other sentence embedding architectures, which might make the design choices for SBERT easier to understand.

InterSent

Conneau et al. created a bi-directional LSTM with max pooling over its outputs to generate sentence embeddings. This model was trained from scratch on both MG-NLI and SNLI datasets which highlight the first difference compared to SBERT. Since BERT is at the core of SBERT does much of its language understanding come from the language modelling pre-training task. SBERT used the MG-NLI and SNLI datasets for fine-tuneing which should allow it to have a better understanding of language.

The LSTM model was able to achieve a test score 84.5 on the SNLI dataset, outperforming at the time best performing competitor with 1.1 points.

Universal Sentence Encoder

Utilising the Transformer architecture enabled Daniel Cer et al. to train a sentence embedding model by averaging the word embeddings created by their Transformer. They also experimented with a Deep Averaging Network (DAN). This model initially average word and bi-gram level embeddings which then would be fed through a feed-forward deep neural network (DNN). One advantage of this approach is that the computational complexity is constant with sequence length, which is not the case for the Transformer. Both these models were trained in a multi-task environment where, to enable different output formats, a task specific DNN was fed the sentence embedding.

Evaluation

The performance of SBERT was evaluated and compared to its competition on two main tasks: Semantic Text Similarity and SentEval, for which there are multiple subtasks. I will highlight the findings I find most interesting, and refer you to the original paper if you want to find out more.

Semantic Textual Similarity

Semantic Textual Similarity (STS) tasks pose a regression problem where the goal is to predict the degree of semantic relatedness between two sentences, which are labeled from 0 to 5. Most related work learn a complex function for this pair-wise mapping, which lead to the combinatorial explosion discussed earlier. SBERT is instead used as a sentence encoder, for which similarity is measured using Spearman correlation between cosine-similarity of the sentence embeddings and the gold labels.

The authors make note of their choice of similarity metric and argue that Pearson correlation (measuring linear relatedness) is less suited for STS when compared to Spearman correlation. The latter measures how well the correlation of two variables can be described by a monotonic function.

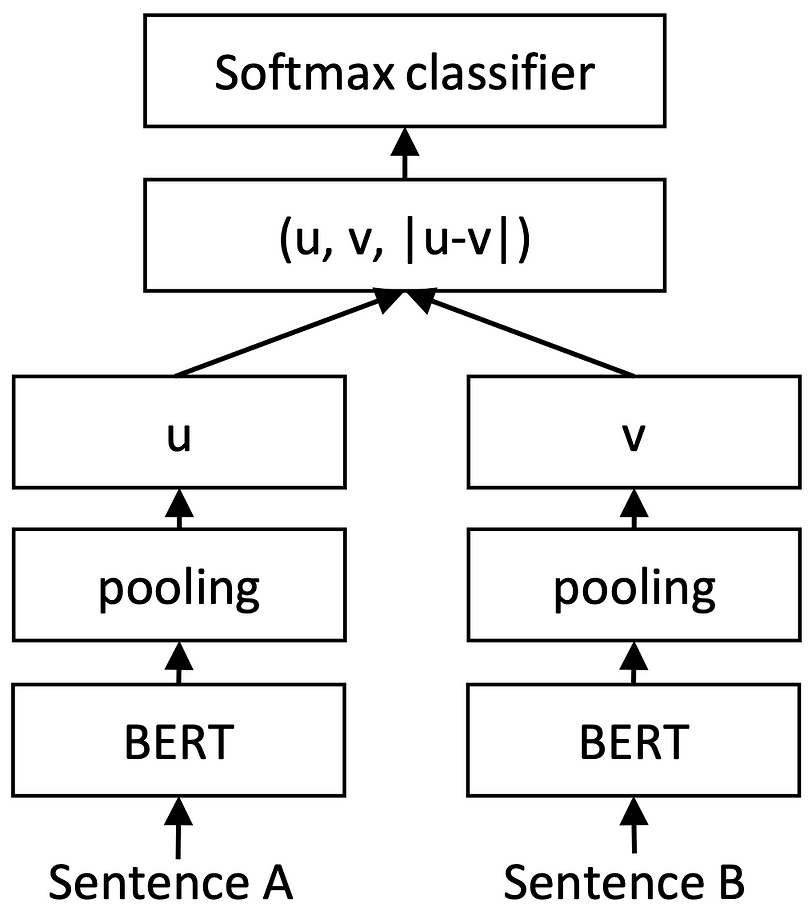

Reimers et al. compared their model in an unsupervised environment, where no STS data was used during pre-training (remember, they only used GM-NLI and SNLI for fine-tuning their already pre-trained BERT architecture). These are their findings:

Performance across seven semantic textual similarity tasks for different sentence embedding models and configurations. Scores are measured in 100 x Spearman correlation.

What is interesting here is that averaging the word embeddings from BERT, or using the CLS token, performs worse than using GloVe embeddings. GloVe embeddings are simple, context aware embeddings created by concatenating a pre-trained, fixed embedding per word with one generated by a bi-directional LSTM. GloVe embeddings are without question outperformed by BERT on token level tasks, but from what is found above, not suited for similarity measures. Worth mentioning is that popular BERT as-a-service generates sentence embeddings in either two of these ways, which from the findings above might be sub-optimal, at least in the setting of STS tasks.

On the other end of the performance spectrum do we find both variations of SBERT, which in the best case perform 63 points better than the above described BERT methods. This impressive difference empirically show that the sentence embeddings created by SBERT is able to capture the semantics of sentences, allowing them to be compared using a measure such as cosine similarity.

What is promising is the fact that these results were achievable in an unsupervised environment. This could imply that similar results are achievable on other datasets, maybe even the one you find most valuable and/or interesting.

The closest competitor, which actually outperforms SBERT on the SICK-R dataset, is the previously described Universal Sentence Encoder (USE). The authors speculate that the reason for this comes from the fact that USE was pre-trained on news datasets, which is similar to that found in SICK-R. SBERT on the other hand, which used Wikipedia and BooksCorpus during pre-training and NLI data for fine-tuning, looses out on domain specific knowledge, which could explain the difference in performance.

Note: SBERT is also benchmarked using to other STS tasks; Argument facet similarity and Wikipedia section distinction. I find these less relevant and will therefore leave it up to you to read more about it, if it seems interesting.

SentEval

The second tasks used to evaluate the performance of SBERT was SentEval. This task, which is an entire toolkit of tasks, is commonly used to evaluate the quality of sentence embeddings. For the subset of tasks selected for evaluation in this paper is it required to train a classifier on top of the generated sentence embeddings. The authors used a logistic regression classifier, with dimensions depending on the dataset at hand which was trained on each task in a 10-fold cross-validation fashion.

Results on seven classification tasks from the SentEval toolkit.

The authors find that SBERT-large achieves the highest average across all tasks, while the smaller SBERT-base is less than three tenths behind. This is a great result when the use-case in mind is time-sensitive, since the smaller model will be much faster to use.

It is also worth noting that the difference between SBERT and the two variations of BERT (avg and CLS) is much smaller here than in previous evaluation. This implies that the embeddings created by BERT can be used as input to a logistic classifier, where each dimension can be treated separately, but not to a cosine similarity function, where the opposite is true. This is quite reassuring since BERT is supposed to create rich token embeddings and intuitively explains the enormous gap in performance found in the previous tasks.

Computational efficiency

We have now observed the performance of SBERT in two different scenarios, which motivate it to be used in various other environments. On example of such, alluded to previously, is semantic search which apart from computational accuracy also requires computational efficiency for being viable in a real-time application.

The authors show that SBERT is comparable, and even competitive, when it comes to speed (measured as sentences it can embed per second). This does however only hold true for SBERT-base (110M parameters), but should not be seen as a deal breaker. Going back over the tables reassures you that the marginal gains (about 1 point difference when looking at the averages) are probably not worth the extra computational complexity.

Computational speed measured in sentences per second.

Conclusion

SentenceBERT introduces pooling to the token embeddings generated by BERT in order for creating a fixed size sentence embedding. When this network is fine-tuned on Natural Language Inference data does it become apparent that it is able to encode the semantics of sentences. These can be used for unsupervised task (semantic textual similarity) or classification problems where they achieve state of the art results.

SBERT is also computationally efficient enabling it to be used in real-time applications such as semantic search. Examples of this will be included in a future article.

Original. Reposted with permission.

About the author: Viktor Karlsson is a Machine Learning Engineer with a growing interest of NLP. Trying to stay on-top of recent developments within the ML field in general, and NLP in particular, with the goal of sharing knowledge and understanding to a wider audience.